Upper Lee

Stella, Lois and Rosemary, reminisce about their grandfather ‘Grampy’ and Grandmother, Henry and Fanny Cooper, and Auntie May, and about life at Upper Lee.

Ro: Leonard (Grampy’s father) was very keen on horses – his father had been a blacksmith and farrier. However, Grampy reputedly hated the things and became mechanised on the farm as soon as possible. He was ahead of his time in so many ways.

Ro: Grampy said that he had one son named biblically (Paul), one named historically (Clive) and a daughter named geographically (Vecta).

Stella: Auntie May used to keep poultry, and she was very fond of guinea fowl as well as hens, and they made lots of racket.

Ro: singing, ‘come back’ – they lived in the orchard, and roosted in the trees – kept clear of foxes.

Stella: Grandma was always extremely mild and never known once to lose her temper. She and Auntie May used to sit in the dining room of a morning and Grampy would bring in all the fruit and veg from the garden, and they’d sit and chat and peel and prep all the veg on newspaper. Everything would be done there and then, straight from the garden ready for lunch, every morning except Sunday. He always had stuff to bring in – still gardening in his 80s!

Stella: tea was just the most incredible meal – eggs, honey in the comb, cucumbers, lettuce, tomato, radishes, fresh white bread – bloomer loaf, and my father being snobbish about my grandfather cutting a doorstep of bread! Fresh butter, cream, strawberries, raspberries, always a lot of fruit. There was always home-made jam and a bowl of honey in the comb on the table.

Ro: children used to come up from the village for Sunday school, and a lot of them used to stay for tea.

Stella: there was an ancient Victorian cooking range in the dining room – often with the smells of roasts and cakes coming out of it, always a warm spot in winter. The irons sat under it.

Ro: the kitchen was known as the brewhouse, I think. You could look straight up the chimney and see the sky, and the fire would sizzle when it rained.

I remember the whiteness of it – whole room was whitewashed.

Stella: there were marble surfaces which were brilliant for pastry. And in the dairy next door there were eggs preserved in isinglass, and big earthenware pots full of salted runner beans for the winter. Washday was a heavy day for all, with a huge mangle in there. There was a butter churn – big barrelled one that sat at an angle, and the chicken feed was stored there too. Ro and I both used to get into trouble for picking out the grains of maize to give to our favourite hens.

Ro: I remember jams being kept in cupboard under the stairs. The cupboard opened from the middle room.

Stella: the stairs were like a spiral, and so decayed that you had to be very careful where you stepped; there were bits of something (asbestos?!) over the holes.

Stella: Grandma and Grampy’s double bed was a genuine feather bed – horse-hair mattress underneath, feather bed on top. All the bedding had to be taken off every day and the bed shaken out, and the sheets checked for little black dots – bed bugs.

Stella: I always thought that everyone had a photographic dark room. Ours was within the centre-front bedroom – beds on the right, bath in front of you, dark room to the left. Uncle Paul (who was the pharmacist in Avenue Road, Freshwater) used it for the pharmacy pictures post-war; it wasn’t until years later that we learnt that Grandma had worked as a photographer’s assistant at the turn of the century.

Ro: The bedroom walls were covered with coloured scraps and pictures cut from magazines (decoupage) – girls with big hats, Dutch skaters, kittens.

Stella: Lying in bed studying the pictures was a very relaxing start to the day. There were very few houses in Thorley with a bath, so they were very proud of it. The bath emptied into the kitchen sink.

Ro and Stella: There was no flushing loo at Upper Lee, just an Elsan in the woodshed that Grampy emptied in a pit he dug in the fields. We think he also spread some of the contents on the garden, as Ro’s mum said that was why the vegetables flourished. There was an eye-level knot hole through which you could watch the cows in the field as you sat inside. It had a stable door, so that you could leave the top door open. Hens were always clucking around, their nest-boxes (old orange boxes) lined one wall. Rain used to drip through the holes in the corrugated roof onto the sawdust below. Every time you went to Upper Lee the holes in the roof were bigger and the corrugated iron lacier.

Ro: on one occasion Auntie May’s bed came through the ceiling – one leg came through the ceiling of the ‘wrong’ room. They’d assumed rooms were properly above each other, but they weren’t, so it didn’t come through where they expected.

Stella: there was the ‘new’ wing (1860s) – which was cold, the stairs were very steep, but it was nice looking out of the gothic window across the fields. The family bible was on a box at the foot of the bed, on top of the trunk.

Christmas at Upper Lee : copyright Cooper family 23 family members for Christmas at Upper lee with Aunt Enid’s cake in the shape of the house.

Ro: at Christmas the sitting room was freezing cold, the fire would be lit after lunch, and it would warm up as everyone opened their presents. There was a photo of the Carl shipwreck in Freshwater Bay dominating one wall, and black lacquer trays hung on others, and the grandfather clock, with fox furs hung over the backs of the seats.

Stella: there was a harmonium in the corner from when it was used for Sunday schools, but also the stereoscope (Lois has it) with slides of Israel – all bible lands. There was the Ship’s cabinet (now with Stella) which had the hymn books in – reputedly hewn from a wreck – could see because it was narrower one side that the other, higher one end than the other, and saw-marks, but with beautiful bevelled glass doors. Grampy loved doing woodwork and amongst his treasures was secret box that you can’t get into – it was like two large books with little books in between, and it was a puzzle box.

Lois: As children, after the morning service, we’d go to Grandad and he’d always give us a peppermint from the tin.

Ro: – little tiny white ones. He always had little black sweets too, called ‘black bobs’, which he said we wouldn’t like (they were liquorice-flavoured). He’d put one in his mouth at bed-time, and he maintained that he could tell the time when we woke up in the night by how small the sweet was. We were horrified, as we thought he shouldn’t have sweets in bed, but it probably didn’t matter as he had no teeth!

Stella: They had a spaniel called Hoppy. Hoppy was a pub dog, and had a barrel rolled over his foot when he was a puppy – named Hoppy for the limp and for the pub!

Ro: when we were children we had a little home-made toy dog, which had a collar embroidered with the name ‘Hoppy’.

Stella: after that was a fox terrier called Judy. One evening I went walking down through Gooseacre with mum and Judy, who caught a rabbit, and my mum took it, killed it in front of me, threaded its legs together and slung it over her shoulder. Not a nice thing to do in front of a six-year-old, I was appalled!

RO: I wasn’t very keen on Judy – kind of jumpy and energetic. Hoppy was lovely – didn’t do anything except sit by the fire.

Stella: My Mum got fined 5 shillings once coming home from work down Wilmingham in the dark (from Freshwater post Office) because her bicycle’s back light was out – a week’s wages for her! Auntie May cycled, and Grampy cycled, but Grandma didn’t.

Ro: Years before, Auntie May used to tow her mother in a carriage (like a basket chair on wheels) attached to the back of the bike. She and Grampy were always great cyclists.

Ro: The grocer, (Mr Higginbotham?), would come in from Yarmouth, come across the fields and sit in the kitchen with Grandma to sort out the grocery order for the week, go back to Yarmouth, and then bring groceries back again. This was some task as the only way to reach the house was over two stiles from the road, across a field, over a railway-sleeper bridge over the brook, up another field and into the garden. There was no vehicular access at all.

Stella: when my Mum was about four she saw a policeman coming over the fields (you had some minutes advance warning) and she got under the table (the same one we’re sitting around now) and cut her hair in the hope that the policeman wouldn’t recognise her. I never did find out what it was a four-year-old could have done that made her feel that guilty.

Stella: Grandma and Auntie May would sit sewing of an evening and made exquisite underwear out of parachute silk, with hand-sewn scalloped edges. You could see diagonal lines where the original stitching had been unpicked. Grampy caught moles, cured skins and they made moleskin mittens. Grampy was ever so proud of the fact that he could knit, and he knitted his own socks, although I never saw him knitting.

Stella: there was always needlework, darning and embroidery, including making brooches out of tiny embroidered flowers. Auntie May did tatting occasionally, which I don’t remember Grandma doing. If not sewing or darning, we would sit round the table of an evening playing Lexicon or Pit.

Stella: I recall sitting quietly on a huge birch bracket fungus in the vegetable garden while Grampy was working, and if I was good he’d turn over part of the compost heap and show me a slowworm.

Ro: I remember we had to be very cautious in the garden and not go near the bee hives.

Stella: that didn’t worry me. I was just worried about the round bed where the well had been in case it opened and swallowed us up. Auntie May had her own cottage garden at the end of the house with asparagus fern, geraniums and carnations.

Stella: Grandad used to take National Geographic magazine, and he used to bind them into yearly hard bound books. He had lots of book binding equipment – wooden press, guillotines. The books were lovely with tooled leather spines.

Ro: On one occasion when he went to the tax office, he went without filling in his forms and he told them that he’d never been to school, so they felt sorry for him and read it all out to him and filled it in for him! Of course, it was true that he’d never been to school, but he was perfectly able to fill in his own tax form.

Stella: Grampy was proud of being well-educated without ever having been to school. They kept up with the news – Grampy had made one of the very first ‘cats whisker’ crystal radio sets and they were regular listeners to the BBC as early as 1924.

Ro: Auntie May had just a short time at primary school, and, being a girl, wouldn’t have had a chance to educate herself. Being from a family of eight children must have been quite hard for all of them.

Ro: Auntie May, Grandma, Grampy: the three of them would do their bible reading together every evening, and Auntie May had trouble with long words and unfamiliar names, and so would say ‘hard word’ when she got to one and then pass straight on.

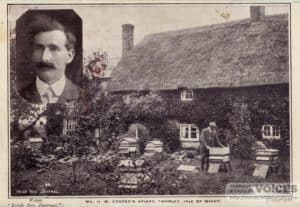

Ro: Grampy became a ‘bee expert’ – did lectures and tours on the mainland. He did meticulous research into Isle of Wight bee disease.

Stella: he was sad all his life because he’d done everything he could to alert bee keepers on the mainland to the dangers of it, and he was mocked by them and told that it was because of their ignorance and dirty bee keeping habits, but it was much more dangerous than they ever thought. It spread through the whole country eventually, as he had warned.

Stella: Grandma used to walk with me across the fields to the railway line and watch the train go past, and pick mushrooms. Grampy used to tell apocryphal tales about the railway – one of his pigs appeared one day with a straight cut across one ear – he reckoned the pig had put its ear to the rail to hear if the train was coming, and got it chopped off! And a fox escaped the hunt across the railway line, and they didn’t catch it; Grampy reckoned he found it a few days later with its sides split – he maintained that it had split its sides laughing!

Ro: Grampy used to tell a lot of funny jokes, but my mum and my brothers and sisters and I couldn’t understand them because he tended to mumble. He became rather deaf as he aged and that was hard for him. He was desperately shy, and didn’t like social occasions, perhaps because his hearing wasn’t up to it.

Stella: During WWII: an incendiary bounced off the thatch and bounced down into a bowl of pears.

Ro: not sure whether it was same occasion, but they could see the waves of incendiaries being dropped across the fields. Grampy wanted to get a ladder from the barn to the house (a two-man job) so that he could sweep them off the thatch if they fell on the house. After that Auntie May always used to run out the door every time she heard an aeroplane and look up to the sky.

He and Grandma were tee-total, and they belonged to the Independent Order of the Rechabites, a temperance friendly society, very much the thing for insurance those days. They were born pre-welfare state and were too old to qualify for a state retirement pension, they were given nothing by the state and had to ensure they had made all their own provision for old age. The honey and vegetables he sold right up until his last days were necessary income.